The weird disappearance of the Sodder Children in West Virginia

Revised October 2023

On Christmas Eve, December 24, 1945, a fire destroyed the home of George and Jennie Sodder in Fayetteville in West Virginia. Nine of their ten children also lived in the house, and four of the nine children escaped the blaze together with their parents. The bodies of the other five children were never found, despite an extensive search of the burnt-out home. Were the remains just missed in the ash, or were they snatched before the house succumbed to the flames?

There are many perplexing clues - Why was the telephone cable cut? Why couldn’t the vehicles on the property be started? Why was the ladder on the house of the house removed and discarded?

Several potential sightings of the missing children were reported in the following years, and a purported photograph of one was sent to the Sodders.

What happened to the Sodder family that night in 1945, just as WW2 had ended?

The Sodder family

George Sodder was born in Tula, Sardinia, in Italy, in 1895, under the name Giorgio Soddu. He emigrated to the USA in 1908 with his older brother, who then returned home after they had cleared customs at Ellis Island in New York, having decided he missed his home far too much.

George found work on the railroads in Pennsylvania, carrying water and other supplies to workers. After a few years, he became a driver in Smithers, West Virginia, and then he started his own trucking company, first carrying fill dirt to construction sites and later transporting coal.

He met Jennie Cipriani, a fellow emigree from Italy and storekeeper's daughter in Smithers, and she later became George's wife, and they married. The couple settled outside nearby Fayetteville, which had a large population of Italian immigrants, in a two-story timber frame house two miles (3.2 km) north of town.

George’s haulage business did well, and in 1923, the couple had the first of their ten children and their last twenty years later, in 1943. The children were John, 23; Marion 17; George Jr, 16; Maurice, 14; Martha 12; Louis, 9; Jennie 8; and Sylvia, the youngest at just 2 years old. Their second oldest son, Joe, had left home to serve in the military during World War II and was still not back in Fayetteville.

George had strong views about his homeland and expressed strong opposition to Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini.

In October 1945, a visiting life insurance salesman warned George that his house "[would go] up in smoke ... and your children are going to be destroyed", attributing this all to "the dirty remarks you have been making about Mussolini."

Another visitor to the house looking for work warned George that a pair of fuse boxes would "cause a fire someday." George was surprised by the comment since he had just rewired the house when an electric stove was installed, and the local electric company had certified it was safe.

In the weeks before Christmas that year, George's older sons had also noticed a strange car parked along the main highway through town, its occupants watching the younger Sodder children as they returned from school.

The Christmas 1945 Sodder house fire

The Sodders spent Christmas Eve 1945 together as a family, and at 10 pm, Jennie told the children they could stay up a little later as long as the two oldest boys who were still awake, Maurice and Louis, remembered to put the cows in and feed the chickens before going to bed. George and the two oldest boys, John and George Jr., who had spent the day working with their father, were already asleep. After reminding the children of those remaining chores, Jennie took the toddler, Sylvia, upstairs, and they went to bed together.

Surprisingly, the telephone rang at 12.30 am on Christmas Day, December 25, 1945, and Jennie was woken up and went downstairs to answer it. The caller was an unknown woman asking for a name she was unfamiliar with, with the sound of laughter and clinking glasses in the background. Jennie told the caller she had dialed the wrong number. Jennie hung up, thinking that the mysterious caller had a weird laugh. Investigators later located the woman who had made the call, and she confirmed it had been a wrong number on her part.

After this phone call, Jennie got up and checked the house and noticed that the lights were still on downstairs and the curtains were not drawn, two things the children usually dealt with when they stayed up later than their parents. Marion had fallen asleep on the living room couch, so Jennie assumed the other children who had stayed up later had returned to the attic where they slept. She closed the curtains, turned out the lights, and returned to bed.

The fire at the Sodder house

At 1.00 am Jennie was woken once more by the sound of an object hitting the house's roof with a loud bang, then a rolling noise. After hearing nothing further, she went back to sleep, thinking it might just be a bird hitting the roof. At 1.30 am, she woke up yet again, smelling smoke. She found that the room George used for his office was on fire, around the telephone line and fuse box, and she quickly woke George Sr. up, and he woke his older children.

George, Jennie, Marion, Sylvia, John, and George Jr. escaped the burning house, but the younger children in the attic had not been able to get out. They tried to reach them, but the stairway was alight and impassable. John said in his first police interview after the fire that he went up to the attic to alert his brothers and sisters sleeping there, though he later changed his story to say that he only called up there and did not see them.

George climbed up the wall of the house and broke open an attic window, cutting his arm in the process. He and his sons intended to use a ladder to the attic to rescue the other children, but it was not in its usual spot resting against the house and could not be found anywhere nearby. A barrel full of water that could have been used to extinguish the fire was frozen solid. George then tried to pull both of the trucks he used in his business up to the house and use them to climb to the attic window, but neither of them would start despite having worked perfectly during the previous day.

For some reason, the phone did not work, so Marion ran to a neighbor's to call the fire department. A neighbor who saw the blaze made a call from a nearby tavern, but again no operator responded. Exasperated, the neighbor drove into town and tracked down Fire Chief F.J. Morris, who initiated Fayetteville’s “phone tree” system whereby one firefighter phoned another, who phoned another. The fire department was only two and a half miles away, but the crew didn’t arrive until 8 am, by which point the Sodders’ home had been more or less destroyed.

The Sodders outside the house were forced to watch in despair as the house burned down during the next hour or two, with the remaining family inside. They assumed the other five children had died in the blaze.

The fire department was undermanned due to WW2 and relied on voluntary firefighters. Chief F.J. Morris said that the already slow response was further hampered by his inability to drive the fire truck, requiring that he wait until someone who could drive was available.

The firefighters, one of whom was a brother of Jennie's, could do little but look through the ashes and dampen down the heat. By 10 am, Chief Morris told the Sodders that they had not found any bones, as might have been expected if the other children had been in the house as it burned. This search and “investigation” must have been limited at best. Nevertheless, Morris believed that the five children unaccounted for had died in the fire, suggesting it had been hot enough to burn their bodies entirely. A state police inspector combed the rubble and attributed the fire to faulty wiring.

The family covered the basement with five feet of dirt, intending to preserve the site as a memorial. But the Sodders’ had begun to wonder if their children were still alive.

The aftermath of the Sodder fire

The local coroner convened an inquest that concluded that the fire was an accident caused by faulty wiring. The jurors included the man who had threatened George with the message that his house would be burned down and his children "destroyed" in retribution for his anti-Mussolini remarks.

Death certificates for the five children were issued on December 30, 1945. George and Jennie were too grief-stricken to attend the funeral on January 2, 1946, although their surviving children did.

What happened to the Sodder House?

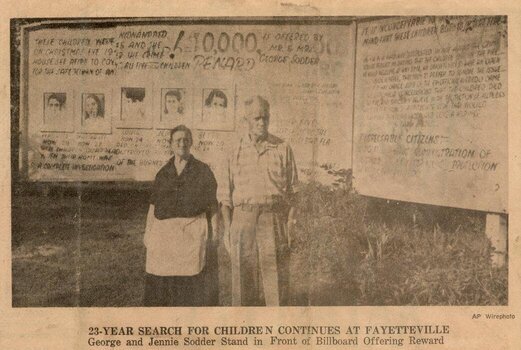

The Sodders never rebuilt the house after the fire and built a memorial garden. In the 1950s, as they came to doubt that the children had perished, the family put up a billboard at the site along State Route 16 with pictures of the five, offering a reward for information. The billboard remained in place until shortly after Jennie Sodder died in 1989.

Sodder house

Suspicions on the fire and deaths

The Sodders pointed out several unusual facts before and during the fire. George disputed the fire department's finding that an electrical fault caused the fire, as he had recently had the house rewired and inspected. The family suspected arson, leading to theories that the children had been taken by the Sicilian Mafia, perhaps in retaliation for George's outspoken criticism of Benito Mussolini and the fascist government of his native Italy.

State and federal efforts to investigate the case further in the early 1950s yielded no new evidence.

Questions about the children and fire at the Sodder property

Where were the children’s bodies - some remains would be expected to be found? Were they really incinerated to ashes?

If an electrical problem caused the fire, why did the family's Christmas lights remain on throughout the fire's early stages when the power should have gone out?

Why had the ladder gone missing from the house, located at the bottom of an embankment 75 feet (23 m) away? Who had removed it?

Why wouldn’t the Sodders’ two vehicles start? The Sodders' trucks' failure to start was thought by the family to be caused by someone tampering with them. One of the sons-in-law of the family told the Charleston Gazette-Mail in 2013 that he had come to believe that Sodder and his sons might have, in their haste to start the trucks, flooded the engines.

Why did the Sodders bulldoze the site so quickly before the official investigation had concluded?

What caused the telephone to be inoperable? A telephone repairman told the Sodders that the house's phone line had not been burned through in the fire, as they had initially thought, but cut by someone who had been willing and able to climb 14 feet (4.3 m) up the pole and reach 2 feet (61 cm) away from it to do so. A man whom neighbors had seen stealing a block and tackle from the property around the time of the fire was identified and arrested. He admitted to the theft and claimed he had been the one who cut the phone line, thinking it was a power line, but denied having anything to do with the fire. However, no record identifying the suspect exists, and why he would have wanted to cut any utility lines to the Sodder house while stealing the block and tackle has never been explained.

What hit the roof at 1 am on December 25? The bus driver that passed through Fayetteville late Christmas Eve said he had seen some people throwing "balls of fire" at the house. This would tie in with Jennie’s recollection of something hitting the roof. A few months later, when the snow had melted, Sylvia found a small, hard, dark green, rubber ball-like object in the brush nearby. George said it looked like a "pineapple bomb" hand grenade or some other incendiary device used in combat. The family later claimed that, contrary to the fire marshal's conclusion, the fire had started on the roof, although by then, there was no way to prove it.

Later developments

Witnesses claimed to have seen the missing children. One woman watching the fire from the road said she had seen some peering out of a passing car while the house burned. Another woman at a rest stop between Fayetteville and Charleston said she had served them breakfast the following day and noted the presence of a car with Florida license plates in the rest stop's parking lot.

The Sodders hired a private investigator named C.C. Tinsley from the nearby town of Gauley Bridge to investigate the case. He learned of rumors around Fayetteville that despite his report to the Sodders that no remains had been found in the ashes, Morris had found a heart, which he later packed into a metal box and secretly buried. Morris had confessed this to a local minister, who confirmed it to George. George and Tinsley went to Morris and confronted him with this news. Morris agreed to show the two where he had buried the metal box, and they dug it up. They took what they found inside the box to a local funeral director, who, after examining it, told them it was, in reality, fresh beef liver that had never been exposed to fire. Later, more rumors circulated Fayetteville that Morris had afterwards admitted the box with the liver had indeed not come from the fire initially. He had supposedly placed it there in the hope that the Sodders would find it and be satisfied that the missing children had indeed died in the fire.

After seeing a girl in a magazine picture of young ballet dancers in New York City who looked like one of his missing daughters, Betty, George drove all the way to the girl's school, where his repeated demands to see the girl himself were refused. He also tried to interest the FBI in investigating what he considered a kidnapping. Director J. Edgar Hoover personally responded to his letters. "Although I would like to be of service", he wrote, "the matter related appears to be of local character and does not come within the investigative jurisdiction of this bureau." If the local authorities requested the bureau's assistance, he added, he would of course, direct agents to assist, but the Fayetteville police and fire departments declined to do so.

In August 1949, George persuaded Oscar Hunter, a Washington, D.C. pathologist, to supervise a new search through the dirt at the house site. After a very thorough search, artefacts including a dictionary that had belonged to the children and some coins, were found. Several small bone fragments were unearthed, determined to have been human vertebrae. The bone fragments were sent to Marshall T. Newman, a specialist at the Smithsonian Institution. They were confirmed to be lumbar vertebrae, all from the same person. "Since the transverse recesses are fused, the age of this individual at death should have been 16 or 17 years", Newman's report said. "The top age limit should be about 22 since the centra, which normally fuse at 23, are still unfused". Thus, given this age range, it was not very likely that these bones were from any of the five missing children since the oldest, Maurice, had been 14 at the time (although the report allowed that vertebrae of a boy his age sometimes were advanced enough to appear to be at the lower end of the range).

Newman added that the bone showed no sign of exposure to flame. Further, he agreed that it was "very strange" that those bones were the only ones found since a wood fire of such short duration should have left full skeletons of all of the children behind. The report concluded that the vertebrae had, instead, most likely come from the dirt that George had bulldozed over the site.

Later, Tinsley supposedly confirmed that the bone fragments had come from a cemetery in nearby Mount Hope but could not explain why they had been taken from there or how they came to be at the fire site. The Smithsonian returned the bone fragments to George in September 1949, according to its records; their current location is unknown.

The West Virginia Legislature held two hearings on the case in 1950. Afterwards, Governor Okey L. Patteson and state police superintendent W.E. Burchett told the Sodders the case was "hopeless" and closed it at the state level. The FBI decided it had jurisdiction as a possible interstate kidnapping but dropped the case after two years.

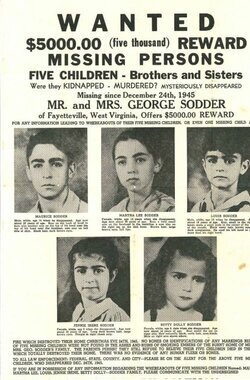

With the end of official efforts to resolve the case, the Sodders printed flyers with pictures of the children, offering a $5,000 then $10,000 reward for information that would have settled the case for even one of them.

The family's efforts soon brought another reported sighting of the children after the fire. Ida Crutchfield, a woman who ran a Charleston hotel, claimed to have seen the children approximately a week afterwards. "I do not remember the exact date", she said in a statement. The children had come in, around midnight, with two men and two women, all of whom appeared to her to be "of Italian extraction". When she attempted to speak with the children, "[o]ne of the men looked at me in a hostile manner; he turned around and began talking rapidly in Italian. Immediately, the whole party stopped talking to me". She recalled that they left the hotel early the following day. Investigators today do not, however, consider her story credible as she had only first seen photos of the children two years after the fire, five years before she came forward.

George followed up on leads in person, traveling to the areas from where tips had come. A woman from St. Louis, Missouri, claimed Martha was being held in a convent there. A bar patron in Texas claimed to have overheard two other people making incriminating statements about a fire that happened on Christmas Eve in West Virginia some years before. None of those proved significant. When George heard later that a relative of Jennie's in Florida had children that looked similar to his, the relative had to prove the children were his own before George was satisfied.

In 1967, George went to the Houston area to investigate another tip. A woman there had written to the family, saying that Louis had revealed his true identity to her one night after having too much to drink. She believed that he and Maurice were both living in Texas somewhere. However, George and his son-in-law, Grover Paxton, could not speak with her. Police there were able to help them find the two men she had indicated, but they denied being the missing sons. Paxton said years later that doubts about that denial lingered in George's mind for the rest of his life.

In 1968, more than 20 years after the fire, Jennie went to get the mail and found an envelope addressed only to her. It was postmarked in Kentucky but had no return address. Inside was a photo of a man in his mid-20s. On its flip side, a cryptic handwritten note read: “Louis Sodder. I love brother Frankie. Ilil Boys. A90132 or 35.” She and George couldn’t deny the resemblance to their Louis, who was 9 at the time of the fire. Beyond the obvious similarities, dark curly hair, dark brown eyes, they had the same straight, strong nose, the same upward tilt of the left eyebrow. Once again, they hired a private detective and sent him to Kentucky.

The photograph sent to Jennie Sodder claiming to be Louis Sodder and at the time of the fire

He never reported back to the Sodders, and they could not locate him afterwards. The picture, nonetheless, gave them hope.

George admitted to the Charleston Gazette-Mail late the following year that the lack of information had been "like hitting a rock wall—we can't go any further". He nevertheless vowed to continue. "Time is running out for us", he admitted in another interview around that time. "But we only want to know. If they did die in the fire, we want to be convinced. Otherwise, we want to know what happened to them".

George Sodder died in 1969, and after his death, Jennie stayed in the family home, putting up fencing around it and adding additional rooms. For the rest of her life, she wore black in mourning and tended the garden at the site of the former house. After she died in 1989, the family finally took the weathered, worn billboard down.

The surviving Sodder children, joined by their children, continued publicizing the case many decades after the fire. The theory prevailed that the Sicilian Mafia was trying to extort money from George, and the children may have been taken by someone who knew about the planned arson and said they would be safe if they left the house. If the children had survived all those years and were aware that their parents and siblings had survived too, the family believes they may have avoided contact to keep them from harm.

Exclusive articles for members of StrangeOutdoors that are not available elsewhere on the site.

See the latest list of Exclusive members-only articles on StrangeOutdoors.com

Read other stories from Strange Indoors

Xavier Dupont de Ligonnès and the Nantes house of horror

The puzzling death of Mateusz Kawecki in Poland

The Olivia Jane Mabel story - supernatural event or viral marketing hoax

The strange disappearance of Dorothy Forstein

The vanishing of Brian Shaffer in the Ugly Tuna Saloona bar in Columbus Ohio

Read other strange stories from Virginia

The bizarre disappearance of Eric Smith from Cedar Bluff in Virginia

The strange disappearance of J.R. Shoemaker from Kirby in Virginia

The disturbing case of James Jordan - The Appalachian Trail Murderer

The unsolved murder of Scott Lilly on the Appalachian trail

Further viewing

BrainScratch: The Sodder Children

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sodder_children_disappearance

https://medium.com/the-true-crime-times/the-sodder-family-a-christmas-inferno-f39f60843412

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-children-who-went-up-in-smoke-172429802/

https://thetruecrimefiles.com/sodder-children-disappearance/

https://defrostingcoldcases.com/case-month-sodder-children/

https://www.appalachianhistory.net/2008/12/something-hit-roof-like-rubber-ball.html