The Flannan Isle Mystery - the mysterious disappearance of the Eilean Mor Lighthouse Keepers

Revised September 2024

On December 26, 1900, a small ship called Hesperus, captained by James Harvie, arrived at the island of Eilean Mòr, the largest of the Flannan Isles in the remote Outer Hebrides, off the north-west coast of Scotland. The island is one of seven islets known to locals as the Seven Hunters, around 17 miles west of the island of Lewis.

The island’s only inhabitants at the time were the lighthouse keepers stationed at the Flannan Isles Lighthouse, near the highest point on the island. Before the arrival of the Hesperus, the steamer Anchtor noted in its log that the lighthouse on Eilean Mòr was not working in bad weather conditions, which was a concern for passing ships that were in danger of crashing onto the rocks.

When the crew of the Hesperus entered the lighthouse, the keepers were nowhere to be seen, and a thorough search of the island turned up no sign. They had mysteriously vanished without a trace.

That visit by Captain Harvie’s ship was to be the start of one of the most enduring and mysterious disappearance mysteries in Scottish history captured in the 2019 film “The Vanishing”.

Did a wave in a storm sweep away the lighthouse keepers on Flannan Island? Or did something darker take place that night?

The history and folklore of Eilean Mòr and the Scottish Hebrides

Sailors feared the Flannans, and often with good cause. Numerous ships had foundered on their jagged coastlines, often hidden by dense fog. In the aftermath of these shipwrecks, their contents and the bodies of victims littered the shores in the vicinity.

Eilean Mòr is named after Flannán mac Toirrdelbaig, an Irish saint who lived in the 7th century and was the son of an Irish chieftain, Turlough of Thomond. He made a pilgrimage to Rome, where Pope John IV consecrated him as the first Bishop of Killaloe, of which he is the Patron Saint.

He built a chapel on the island, and in death, he was said to regard Eilean Mòr as his own. For centuries, shepherds used to bring sheep to the island to graze but would never stay the night, fearful of the spirits that were believed to haunt it. A sinister, watchful presence was said to reside there.

Although the island seemed the perfect place to establish a congregation, the worshipers believed in the island’s supernatural powers. It was a place that many still believe was a place of fairies. Because of its reputation and the superstition surrounding it, the locals adopted rituals such as circling the church on your knees. It was said there was a definite presence of an aura that undeniably shrouded the island.

According to a history of Scotland's Western Isles, written in 1695, "these remote islands were places of inherent sanctity", and there was a custom that arriving on the island would "uncover their heads and make a turn sun-ways round, thanking God for their safety".

There were reports of human sacrifices at Calanais (Callanish) on nearby Lewis (Eilean Siar), a place that has standing stones, from around 3,000 BC. A ring of gneiss slabs surrounding a central monolith, with an avenue running north and single rows extending south, east, and west, is older than Stonehenge.

While it was most likely an astronomical observatory, it was probably also a place of ritual activity.

CALANAIS STANDING STONES LEWIS

The Hebrides were once believed to be home to a race of tiny, pixie-ish men, and Lewis was known as "the Pigmie Isle". On early Ordnance Survey maps, it is called Luchruban, apparently a variation of "leprechaun."

The construction of the Flannan Isles Lighthouse

When the lighthouse was built in December 1899 to guide ships through one of the wildest parts of the North Atlantic, locals in the Flannans warned that the intrusion would unleash St Flann’s wrath.

David Alan Stevenson, the son of Treasure Island author Robert Louis Stevenson, designed the twenty-three meter (75 ft) lighthouse for the Northern Lighthouse Board (NLB). He warned the board that "there is little protection from the Atlantic swell, which is seldom at rest".

Construction occurred between 1895 and 1899 by George Lawson of Rutherglen for £1,899, including the building of the landing places, stairs, and railway tracks. All materials had to be moved up the 45-meter (148 ft) cliffs directly from supply boats. A further £3,526 was spent on the shore station at Breasclete on the Isle of Lewis. It was first lit on 7 December 1899.

The purpose of the railway tracks was to help transport provisions for the keepers and paraffin fuel for the light on the lighthouse. It burnt twenty barrels of paraffin a year, which had to be carried up steep gradients from the landing places using a cable-hauled railway—a small steam engine powered this in a shed next to the lighthouse. A track came down from the lighthouse in a westerly direction and then curved around to the south. In the approximate center of the island, it forked using a set of hand-operated points called "Clapham Junction", named after the railway junction in central London; one branch continued in its curvature to head eastwards to the east landing place, on the south-east corner of the island, forming a half-circle, while the other, slightly shorter, branch curved back to the west to serve the west landing, situated in a small inlet on the island's south coast.

In 1925, the lighthouse was one of the first Scottish lighthouses to receive communications from the shore by wireless telegraphy. In the 1960s, the island's transport system was modernized. The railway was removed, leaving behind the concrete bed on which it had been laid to serve as a roadway for a "Gnat" – a three-wheeled, rubber-tired cross-country vehicle powered by a 400-cubic-centimetre (24 cu in) four-stroke engine, built by Aimers McLean of Galashiels. This had a shorter working life than the railway, becoming redundant when the helipad was constructed for helicopter transport.

On 28 September 1971, the lighthouse was automated. The light is now produced by burning acetylene gas and has a range of 17 nautical miles, 20 miles (32 km). It is monitored from the Butt of Lewis, and the shore station has been converted into apartments.

The life of a lighthouse keeper in the 19th and 20th centuries

According to the Northern Lighthouse Board (NLB), who are the General Lighthouse Authority responsible for the waters surrounding Scotland and the Isle of Man.: “Our mission as a General Lighthouse Authority is to deliver in the most sustainable, practicable, reliable, efficient, and cost-effective Aids to Navigation service for the benefit and safety of all Mariners.”

Lightkeepers were divided into two grades – Principal Lightkeeper and Assistant Lightkeeper. Their primary duties were to keep the light and fog signal in perfect working order. At night, Keepers took turns watching in the lightroom to ensure the light was working correctly. The hours for this varied depending on the type of station. During the daytime, all Keepers cleaned, painted and generally kept the premises clean and tidy. At Rock Stations such as the Bell Rock or Skerryvore, there were six Lightkeepers (three on the Rock and three having a spell ashore) and four at Mainland Fog Signal Stations.

On March 31, 1998, over 211 years of Lightkeeping tradition ended in Scotland when Fair Isle South became its last manned lighthouse.

The life of a Lightkeeper could be lonely except in those cases where the lighthouse station was situated near a town or village.

At Rock and Relieving Stations, the Keepers were especially isolated. They were on duty at these stations for four weeks, followed by four weeks ashore. The families lived in houses at the “Shore Station”, which were provided for them. At land-based stations, the wives and families of career Lightkeepers lived with them at the light stations.

Not every person was suitable to be a Lightkeeper. The good Lightkeeper had or acquired the temperament necessary for this job, which involved residence close to the sea and had much loneliness and isolation in its composition.

While primary duties were to keep watch at night, to ensure the light flashed correctly to character, and to keep a fog watch every 24 hours to be ready to operate the fog signal in the event of poor visibility, a Lightkeeper must be a man of parts. He would acquire a good working knowledge of engines. At stations with Radio Beacons and Radar Beacons, he would initially be responsible for their accurate operation. He would know about Radio Telephones; from his study of the sea, he would respect its immense power; he would be a handyman of varying proficiency but mainly of a high standard; he would be a good cook and companion.

A Lightkeeper would not make a fortune, but the odds are he would be at peace with himself and the world.

The Eilean Mòr lighthouse keepers

(from left to right) Thomas Marshall, Donald MacArthur and James Ducat - December 8, 1900

The lighthouse was manned and operated by three men:

Principal Keeper James Ducat, 43

Assistant Lightkeeper Thomas Marshall, 40

Occasional Keeper Donald William McArthur, 28

The lighthouse should have had four staff members, but one, William Ross, was away due to sickness, and another, Joseph Moore, was on shore leave. MacArthur, who had signed up earlier that year as an occasional lightkeeper, was called in to help Ducat and Marshall.

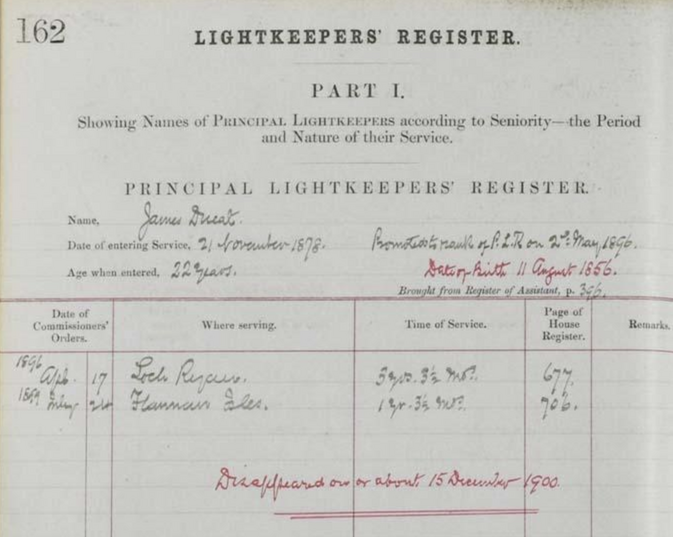

James Ducat was the Principal Lightkeeper on duty at the time. The Lightkeeper Registers state Ducat entered the service on November 21, 1878, aged 22. As an Assistant Lightkeeper, he worked on Montroseness, Inchkeith, Rhins of Islay and Langness. On May 2, 1896, he was promoted to Principal Keeper at Loch Ryan and finally served on the Flannan Isles. The final entry in the register has noted underneath it, “Disappeared on or about 15 December 1900”.

Information recorded on Thomas Ducat’s time as a Principal Lightkeeper in the Lightkeeper Registers. Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, NLC4/1/3 (page 162)

In 1990, his daughter 98-year-old, Anna Ducat, gave an interview to The Times in which she recalled her father's reluctance to take the post, "He said it was too dangerous, that he had a wife and four children depending on him, but Mr Muirhead (Robert Muirhead - the superintendent) persuaded him because he had such faith in him as a good and reliable keeper”. On the day he left for the last time, he stopped to give each of his children a kiss, "I always wondered if he had some kind of premonition that he would never see us again."

Working with Ducat was Thomas Marshall, a large man seen as a "gentle giant" by locals, who was still in his twenties but had four years of lighthouse experience.

Donald MacArthur was a local tailor who had served in the Royal Engineers and was said to have a nasty temper.

The Hesperus and Eilean Mòr lighthouse in December 1900

The first record that something was not right on the island was on December 15-16, 1900, when the steamer SS Archtor, on a voyage from Philadelphia to Leith in Scotland, noted in its log that the light was not working in poor weather conditions.

Board superintendent Robert Muirhead, who was later tasked with investigating their disappearance, had visited the lighthouse at the beginning of December and found nothing unusual. "I have the melancholy recollection that I was the last person to shake hands with them and bid them adieu," he later wrote.

Subsequent investigations showed that the lighthouse itself was not seen, even with the assistance of a powerful telescope, between the 7th and the 29th of December. However, The light was observed on December 7 but not on the 8th, 9th, 10th and 11th. It was seen on the 12th but not seen again until the 26th. Sometimes, due to weather, the lights were not seen for four of five consecutive nights, but the long duration was a surprising occurrence that raised alarm in Leith.

When the ship docked in Leith on 18 December 1900, the sighting was passed onto the Northern Lighthouse Board (NLB) after some delay. The relief vessel, the lighthouse tender Hesperus, could not sail from Breasclete, Lewis, as planned on December 20 due to bad weather, and it did not reach the island until noon on December 26.

On arrival, the crew and relief keeper found that the flagstaff had no flag, all of the usual provision boxes had been left on the landing stage for re-stocking, and none of the lighthouse keepers were there to welcome them ashore. Thomas Marshall, Donald MacArthur and James Ducat were nowhere to be seen.

A poem about the incident, written in 1912 by Wilfrid Wilson Gibson, describes an untouched meal on the table — cold meat, pickles and potatoes. A kitchen chair lay on its side, and the only sign of life was the keepers’ canary, half-starving on its perch. However, the details from Gibson’s poem should be taken with a pinch of salt and are unlikely to be a factual account of the lighthouse scene.

James Harvie, the Captain of Hesperus, attempted to reach them by blowing the ship's whistle and firing a flare, but there was no response.

A boat was launched, and Joseph Moore, who should have been at the lighthouse but was on leave and returned aboard the Hesperus, was put ashore alone, rowed ashore, and took the steep stairs leading up to the lighthouse. It is said that he suffered an overwhelming sense of foreboding on his walk up to the top of the cliff. He found the entrance gate to the compound and the main door both unlocked, the beds unmade, and the clock on the wall had stopped as if some evil force had stopped time in its tracks. However, Moore also stated that everything looked orderly, and "the kitchen utensils were all very clean”, which counters the narrative.

Returning to the landing stage with this grim news, he returned to the lighthouse with Hesperus' second mate and a seaman. A further search revealed that the lamps had been cleaned and refilled. There was no sign of any keepers inside the lighthouse or on the island.

The men scoured every part of the island for clues as to the fate of the keepers. They found that everything was intact at the east landing, but the west landing provided evidence of damage caused by recent storms. A box at 33 metres (108 ft) above sea level had been broken, and its contents were thrown around. Iron railings were bent over, the iron railway by the path was wrenched out of its concrete, and a rock weighing more than a ton had been displaced. On top of the cliff at more than 60 metres (200 ft) above sea level, turf had been ripped away as far as 10 metres (33 ft) from the cliff edge.

Reluctantly, Moore agreed to stay and tend the light, given that the keepers could not be located when Hesperus left the island. It’s not difficult to imagine how scary the following nights were for him, alone in the light room, listening to the wind howling all around as the revolving lamp cast shadows.

Moore later wrote on December 28, 1900:

“Sir, It was with deep regret I wish you to learn the very sad affair that has taken place here during the past fortnight; namely the disappearance of my two fellow lightkeepers Mr Ducat and Mr Marshall, together with the Occasional Keeper, Donald McArthur from off this Island.

As you are aware, the relief was made on the 26th. That day, as on other relief days, we came to anchorage under Flannan Islands, and not seeing the Lighthouse Flag flying, we thought they did not perceive us coming. The steamer’s horn was sounded several times, still no reply. At last Captain Harvie deemed it prudent to lower a boat and land a man if it was possible. I was the first to land leaving Mr McCormack and his men in the boat till I should return from the lighthouse. I went up, and on coming to the entrance gate I found it closed. I made for entrance door leading to the kitchen and store room, found it also closed and the door inside that, but the kitchen door itself was open. On entering the kitchen I looked at the fireplace and saw that the fire was not lighted for some days. I then entered the rooms in succession, found the beds empty just as they left them in the early morning.

I did not take time to search further, for I only too well knew something serious had occurred. I darted out and made for the landing. When I reached there I informed Mr McCormack that the place was deserted. He with some of the men came up second time, so as to make sure, but unfortunately the first impression was only too true. Mr McCormack and myself proceeded to the lightroom where everything was in proper order. The lamp was cleaned. The fountain full. Blinds on the windows etc. We left and proceeded on board the steamer. On arrival Captain Harvie ordered me back again to the island accompanied with Mr McDonald (Buoymaster), A Campbell and A Lamont who were to do duty with me till timely aid should arrive. We went ashore and proceeded up to the lightroom and lighted the light in the proper time that night and every night since. The following day we traversed the Island from end to end but still nothing to be seen to convince us how it happened. Nothing appears touched at East landing to show that they were taken from there. Ropes are all in their respective places in the shelter, just as they were left after the relief on the 7th.

On West side it is somewhat different. We had an old box halfway up the railway for holding West landing mooring ropes and tackle, and it has gone. Some of the ropes it appears, got washed out of it, they lie strewn on the rocks near the crane. The crane itself is safe.

The iron railings along the passage connecting railway with footpath to landing and started from their foundation and broken in several places, also railing round crane, and handrail for making mooring rope fast for boat, is entirely carried away. Now there is nothing to give us an indication that it was there the poor men lost their lives, only that Mr Marshall has his seaboots on and oilskins, also Mr Ducat has his seaboots on. He had no oilskin, only an old waterproof coat, and that is away. Donald McArthur has his wearing coat left behind him which shows, as far as I know, that he went out in shirt sleeves. He never used any other coat on previous occasions, only the one I am referring to.”

Captain Harvey sent a telegram to the Northern Lighthouse Board dated 26 December 1900, stating:

“A dreadful accident has happened at the Flannans. The three keepers, Ducat, Marshall and the Occasional have disappeared from the Island.

Fired a rocket but, as no response was made, managed to land Moore, who went up to the Station but found no Keepers there. The clocks were stopped and other signs indicated that the accident must have happened about a week ago. Poor fellows they must been blown over the cliffs or drowned trying to secure a crane or something like that. Night coming on, we could not wait to make something as to their fate.

I have left Moore, MacDonald, Buoymaster and two Seamen on the island to keep the light burning until you make other arrangements. Will not return to Oban until I hear from you. I have repeated this wire to Muirhead in case you are not at home. I will remain at the telegraph office tonight until it closes, if you wish to wire me.”

The Northern Lighthouse Board’s superintendent, Robert Muirhead, arrived three days later to investigate and described Moore as being in a state of ‘nervousness’.

Muirhead, both recruited and knew all three men personally, departed for the island to investigate the disappearances. He last saw the keepers on December 7, when he travelled out for a routine check on his employees. ‘I have the melancholy recollection that I was the last person to shake hands with them and bid them adieu,’ he wrote.

His investigation of the lighthouse found nothing over and above what Moore had already reported. That is, except for the lighthouse log.

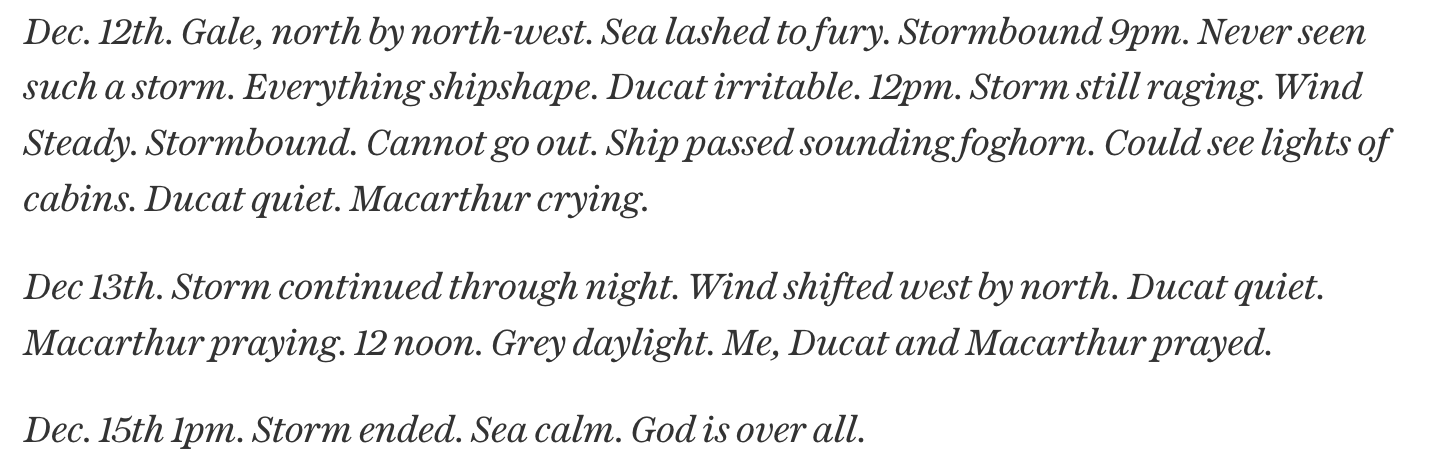

Muirhead immediately noticed that the last few days of entries were unusual. On the 12th of December, Thomas Marshall, the second assistant, wrote of ‘severe winds the likes of which I have never seen before in twenty years’. He also noticed that James Ducat, the Principal Keeper, had been ‘very quiet’ and that the third assistant, William McArthur, had been crying.

Strangely, there were no reported storms in the island area during that period. The weather was said to be calm, and the storms only hit the island on December 17th.

What is also mysterious is that William McArthur was an experienced mariner and lighthouse man known on the mainland as a strict sort. Why would he be concerned about a storm, even a bad one?

Log entries on December 13, 1900, said that the storm was still ravaging the island and that all three men had been praying. Three experienced lighthouse men praying? The storm must indeed have been dreadful for these seasoned men.

The last record left by the men was on the morning of December 15, 1990, chalked on the slate where they noted weather conditions and their daily activities, including trimming the lighthouse lamp, filling its oil fountains and cleaning the giant lenses. Nothing amiss was mentioned, but the fact that the lighthouse had not been operational that evening strongly implied that this was the day they disappeared. The final log entry said, “Storm ended, sea calm. God is over all”.

After reading the logs, Muirhead’s investigations turned to the oil-skinned coat left in the entrance hall. Why had one of the lighthouse keepers left the warmth to venture outside without his coat in the freezing winter temperatures? Furthermore, why did all three lighthouse staff leave their posts simultaneously when rules and regulations strictly prohibited it?

Flannan Isles Lighthouse on Eilean Mòr

Further clues were found during the investigation down by the landing platform. Muirhead noticed ropes strewn all over the rocks, usually held in a brown crate 70 feet above the platform on a supply crane. Perhaps the crate had been dislodged and knocked down, and the lighthouse keepers were attempting to retrieve them when an unexpected wave came and washed them out to sea. This was his preferred theory to explain the disappearances, and he stated this in his official report to the Northern Lighthouse Board.

He reported, “I am of the opinion that the most likely explanation of this disappearance of the men is that they had all gone down on the afternoon Saturday, 15 December…and a large body of water…coming down upon them had swept them away with resistless force.”

While keeper Thomas Marshall was single, the other two — James Ducat and Donald MacArthur were married, with six children between them. The task of breaking the news to their widows had fallen to Muirhead, who knew their families well.

Report submitted by Robert Muirhead, Superintendent, on January 8, 1901

On receipt of Captain Harvie’s telegram on 26 December 1900 reporting that the three keepers on Flannan Islands, viz James Ducat, Principal, Thomas Marshall, second Assistant, and Donald McArthur, Occasional Keeper (doing duty for William Ross, first Assistant, on sick leave), had disappeared and that they must have been blown over the cliffs or drowned, I made the following arrangements with the Secretary for the temporary working of the Station.

James Ferrier, Principal Keeper, was sent from Stornoway Lighthouse to Tiumpan Head Lighthouse and John Milne, Principal Keeper at Tiumpan Head, was sent to take temporary charge at Flannan Islands. Donald Jack, the second Assistant Storekeeper, was also despatched to Flannan Islands, the intention being that these two men, along with Joseph Moore, the third Assistant at Flannan Islands, who was ashore when the accident occurred, should do duty pending permanent arrangements being made. I also proceeded to Flannan Islands where I was landed, along with Milne and Jack, early on the 29th.

After satisfying myself that everything connected with the light was in good order and that the men landed would be able to maintain the light, I proceeded to ascertain, if possible, the cause of the disaster and also took statements from Captain Harvie and Mr McCormack the second mate of the HESPERUS, Joseph Moore, third Assistant keeper, Flannan Islands and Allan MacDonald, Buoymaster and the following is the result of my investigations:-

The HESPERUS arrived at Flannan Islands for the purpose of making the ordinary relief about noon Wednesday, 26 December and, as neither signals were shown, nor any of the usual preparations for landing made, Captain Harvie blew both the steam whistle and the siren to call the attention of the Keepers. As this had no effect, he fired a rocket, which also evoked no response, and a boat was lowered and sent ashore to the East landing with Joseph Moore, Assistant Keeper. When the boat reached the landing there being still no signs of the keepers, the boat was backed into the landing and with some difficulty, Moore managed to jump ashore. When he went up to the Station, he found the entrance gate and outside doors closed, the clock stopped, no fire lit, and, looking into the bedrooms, he found the beds empty. He became alarmed at this and ran down to the boat and informed Mr McCormack, and one of the seamen managed to jump ashore and, with Moore made a thorough search of the Station but could discover nothing. They then returned to the ship and informed Captain Harvie, who told Moore he would have to return to the Island to keep the light going pending instructions, and called for volunteers from his crew to assist in this.

He met with a ready response, and two seamen, Lamont and Campbell, were selected with Mr MacDonald, the Buoymaster, who was on board, also offered his services, which were accepted and Moore, MacDonald, and these two seamen were left in charge of the light while Captain Harvie returned to Breasclete and telegraphed an account of the disaster to the Secretary.

The men left on the Island made a thorough search, in the first place, of the Station and found that the last entry on the slate had been made by Mr Ducat, the Principal Keeper, on the morning of Saturday, 15 December. The lamp was crimped, the oil fountains and canteens were filled up and the lens and machinery cleaned, which proved that the work of the 15th had been completed. The pots and pans had been cleaned and the kitchen tidied up, which showed that the man who had been acting as cook had completed his work, which goes to prove that the men disappeared on the afternoon which was received (after news of the disaster had been published) that Captain Holman had passed the Flannan Islands in the steamer ARCHTOR at midnight on the 15th ulto, and could not observe the light, he felt satisfied that he should have seen it.

On the Thursday and Friday the men made a thorough search over and round the island and I went over the ground with them on Saturday. Everything at the East landing place was in order and the ropes which had been coiled and stored there on the completion of the relief on 7 December were all in their places, and the lighthouse buildings and everything at the Stations was in order. Owing to the amount of sea, I could not get down to the landing place, but I got down to the crane platform 70 feet above the sea level. The crane originally erected on this platform was washed away during last winter, and the crane put up this summer was found to be unharmed, the jib lowered and secured to the rock, and the canvas covering the wire rope on the barrel securely lashed round it, and there was no evidence that the men had been doing anything at the crane. The mooring ropes, landing ropes, derrick landing ropes and crane handles, and also a wooden box in which they were kept and which was secured in a crevice in the rocks 70 feet up the tramway from its terminus, and about 40 feet higher than the crane platform, or 110 feet in all above the sea level, had been washed away, and the ropes were strewn in the crevices of the rocks near the crane platform and entangled among the crane legs, but they were all coiled up, no single coil being found unfastened. The iron railings round the crane platform and from the terminus of the tramway to the concrete steps up from the West landing were displaced and twisted. A large block of stone, weighing upwards of 20 cwt, had been dislodged from its position higher up and carried down to and left on the concrete path leading from the terminus of the tramway to the top of the steps.

A life buoy fastened to the railings along this path, to be used in case of emergency had disappeared, and I thought at first that it had been removed for the purpose of being used but, on examining the ropes by which it was fastened, I found that they had not been touched, and as pieces of canvas was adhering to the ropes, it was evident that the force of the sea pouring through the railings had, even at this great height (110 feet above sea level) torn the life buoy off the ropes.

When the accident occurred, Ducat was wearing sea boots and a waterproof, and Marshall sea boots and oilskins, and as Moore assures me that the men only wore those articles when going down to the landings, they must have intended, when they left the Station, either to go down to the landing or the proximity of it.

After a careful examination of the place, the railings, ropes etc and weighing all the evidence which I could secure, I am of opinion that the most likely explanation of the disappearance of the men is that they had all gone down on the afternoon of Saturday, 15 December to the proximity of the West landing, to secure the box with the mooring ropes, etc and that an unexpectedly large roller had come up on the Island, and a large body of water going up higher than where they were and coming down upon them had swept them away with resistless force.

I have considered and discussed the possibility of the men being blown away by the wind, but, as the wind was westerly, I am of the opinion, notwithstanding its great force, that the more probably explanation is that they have been washed away as, had the wind caught them, it would, from its direction, have blown then up the Island and I feel certain that they would have managed to throw themselves down before they had reached the summit or brow of the Island.

On the conclusion of my enquiry on Saturday afternoon, I returned to Breasclete, wired the result of my investigations to the Secretary and called on the widows of James Ducat, the Principal Keeper and Donald McArthur, the Occasional Keeper.

I may state that, as Moore was naturally very much upset by the unfortunate occurrence, and appeared very nervous, I left A Lamont, Seaman, on the Island to go to the lightroom and keep Moore company when on watch for a week or two.

If this nervousness does not leave Moore, he will require to be transferred, but I am reluctant to recommend this, as I would desire to have one man at least who knows the work of the Station.

The Commissioners appointed Roderick MacKenzie, Gamekeeper, Uig, near Meavaig, to look out daily for signals that might be shown from the Rock, and to note each night whether the light was seen or not seen. As it was evident that the light had not been lit from the 15th to the 25th December, I resolved to see him on Sunday morning, to ascertain what he had to say on the subject. He was away from home, but I found his two sons, ages about 16 and 18 – two most intelligent lads of the gamekeeper class, and who actually performed the duty of looking out for signals – and had a conversation with them on the matter, and I also examined the Return Book. From the December Return, I saw that the Tower itself was not seen, even with the assistance of a powerful telescope, between the 7th and the 29th December. The light was, however, seen on 7th December, but was not seen on the 8th, 9th, 10th and 11th. It was seen on the 12th, but not seen again until the 26th, the night on which it was lit by Moore. MacKenzie stated (and I have since verified this), that the lights sometimes cannot be seen for four of five consecutive nights, but he was beginning to be anxious at not seeing it for such a long period, and had, for two nights prior to its reappearance, been getting the assistance of the natives to see if it could be discerned.

Had the lookout been kept by an ordinary Lightkeeper, as at Earraid for Dubh Artach, I believe it would have struck the man ashore at an earlier period that something was amiss, and, while this would note have prevented the lamentable occurrence taking place, it would have enabled steps to have been taken to have the light re-lit at an earlier date. I would recommend that the Signalman should be instructed that, in future, should he fail to observe the light when, in his opinion, looking to the state of the atmosphere, it should be seen, he should be instructed to intimate this to the Secretary, when the propriety of taking steps could be considered.

I may explain that signals are shown from Flannan Islands by displaying balls or discs each side of the Tower, on poles projecting out from the Lighthouse balcony, the signals being differentiated by one or more discs being shown on the different sides of the Tower. When at Flannan Islands so lately as 7th December last, I had a conversation with the late Mr Ducat regarding the signals, and he stated that he wished it would be necessary to hoist one of the signals, just to ascertain how soon it would be seen ashore and how soon it would be acted upon.

At that time, I took a note to consider the propriety of having a daily signal that all was well – signals under the present system being only exhibited when assistance of some kind is required. After carefully considering the matter, and discussing it with the officials competent to offer an opinion on the subject, I arrived at the conclusion that it would not be advisable to have such a signal, as, owing to the distance between the Island and the shore, and to the frequency of haze on the top of the Island, it would often be unseen for such a duration of time as to cause alarm, especially on the part of the Keepers’ wives and families, and I would point out that no day signals could have been seen between the 7th and 29th December, and an “All Well” signal would have been of no use on this occasion.

The question has been raised as to how we would have been situated had wireless telegraphy been instituted, but, had we failed to establish communication for some days, I should have concluded that something had gone wrong with the signalling apparatus, and the last thing that would have occurred to me would have been that all the three men had disappeared.

In conclusion, I would desire to record my deep regret at such a disaster occurring to Keepers in this Service. I knew Ducat and Marshall intimately and McArthur the Occasional, well. They were selected, on my recommendation, for the lighting of such an important Station as Flannan Islands, and as it is always my endeavour to secure the best men possible of the establishment of a Station, as the success and contentment at a Station depends largely on the Keepers present at its installation, this of itself is an indication that the Board has lost two of it most efficient Keepers and a competent Occasional.

I was with the Keepers for more than a month during the summer of 1899, when everyone worked hard to secure the early lighting of the Station before winter, and, working along with them, I appreciated the manner in which they performed their work. I visited Flannan Islands when the relief was made so lately as 7th December and have the melancholy recollection that I was the last person to shake hands with them and bid them adieu.

Wilfrid Wilson Gibson's “Flannan Isle” poem

"Flannan Isle" is a poem by Wilfrid Wilson Gibson, first published in 1912, that refers to the disappearance of the Eilean Mor Lighthouse Keepers on the Flannan Isle.

“THOUGH three men dwell on Flannan Isle

To keep the lamp alight,

As we steered under the lee, we caught

No glimmer through the night.”

A passing ship at dawn had brought

The news; and quickly we set sail,

To find out what strange thing might ail

The keepers of the deep-sea light.

The Winter day broke blue and bright,

With glancing sun and glancing spray,

As o’er the swell our boat made way,

As gallant as a gull in flight.

But, as we neared the lonely Isle;

And looked up at the naked height;

And saw the lighthouse towering white,

With blinded lantern, that all night

Had never shot a spark

Of comfort through the dark,

So ghostly in the cold sunlight

It seemed, that we were struck the while

With wonder all too dread for words.

And, as into the tiny creek

We stole beneath the hanging crag,

We saw three queer, black, ugly birds—

Too big, by far, in my belief,

For guillemot or shag—

Like seamen sitting bolt-upright

Upon a half-tide reef:

But, as we neared, they plunged from sight,

Without a sound, or spurt of white.

And still to mazed to speak,

We landed; and made fast the boat;

And climbed the track in single file,

Each wishing he was safe afloat,

On any sea, however far,

So it be far from Flannan Isle:

And still we seemed to climb, and climb,

As though we’d lost all count of time,

And so must climb for evermore.

Yet, all too soon, we reached the door—

The black, sun-blistered lighthouse-door,

That gaped for us ajar.

As, on the threshold, for a spell,

We paused, we seemed to breathe the smell

Of limewash and of tar,

Familiar as our daily breath,

As though ‘t were some strange scent of death:

And so, yet wondering, side by side,

We stood a moment, still tongue-tied:

And each with black foreboding eyed

The door, ere we should fling it wide,

To leave the sunlight for the gloom:

Till, plucking courage up, at last,

Hard on each other’s heels we passed,

Into the living-room.

Yet, as we crowded through the door,

We only saw a table, spread

For dinner, meat and cheese and bread;

But, all untouched; and no one there:

As though, when they sat down to eat,

Ere they could even taste,

Alarm had come; and they in haste

Had risen and left the bread and meat:

For at the table-head a chair

Lay tumbled on the floor.

We listened; but we only heard

The feeble cheeping of a bird

That starved upon its perch:

And, listening still, without a word,

We set about our hopeless search.

We hunted high, we hunted low;

And soon ransacked the empty house;

Then o’er the Island, to and fro,

We ranged, to listen and to look

In every cranny, cleft or nook

That might have hid a bird or mouse:

But, though we searched from shore to shore,

We found no sign in any place:

And soon again stood face to face

Before the gaping door:

And stole into the room once more

As frightened children steal.

Aye: though we hunted high and low,

And hunted everywhere,

Of the three men’s fate we found no trace

Of any kind in any place,

But a door ajar, and an untouched meal,

And an overtoppled chair.

And, as we listened in the gloom

Of that forsaken living-room—

A chill clutch on our breath—

We thought how ill-chance came to all

Who kept the Flannan Light:

And how the rock had been the death

Of many a likely lad:

How six had come to a sudden end,

And three had gone stark mad:

And one whom we’d all known as friend

Had leapt from the lantern one still night,

And fallen dead by the lighthouse wall:

And long we thought

On the three we sought,

And of what might yet befall.

Like curs, a glance has brought to heel,

We listened, flinching there:

And looked, and looked, on the untouched meal,

And the overtoppled chair.

We seemed to stand for an endless while,

Though still no word was said,

Three men alive on Flannan Isle,

Who thought, on three men dead.”

Questions on the mysterious story of the Eilean Mor disappearances

Why had none of the bodies been washed ashore if they had been washed out to sea?

Why had one of the men left the lighthouse without taking his coat?

Why had three experienced lighthouse keepers been taken unaware by a freak wave?

The seas were calm, according to reports from nearby islands. Why did the men write in the log that a terrible storm beset them?

Possible explanations for the disappearances of Thomas Marshall, Donald MacArthur and James Ducat

Washed away by the storm or a sudden gust of wind

Muirhead noted that the landing platform on the island's western side had suffered severe storm damage, with twisted iron railings and a block of stone, estimated to weigh a ton, displaced onto the path. He concluded that the men must have gone to repair the damage and been swept away by a wave.

On December 15, according to contemporary weather reports, the gale reached force eight on the Beaufort scale. But Muirhead dismissed this idea in his original 1901 report: "As the wind was westerly, I am of opinion, notwithstanding its great force, that [...] it would, from its direction, have blown them up the island."

But why did all three men disappear? While the boots, coats, and oilskins belonging to Ducat and Marshall were missing, Donald MacArthur’s remained inside the lighthouse. It seems unlikely that, in the freezing weather, he would have left the lighthouse wearing only shirt-sleeves and rope-soled sandals.

It was possible, of course, that Ducat and Marshall had run into trouble at the landing stage and that, on hearing their cries for help, MacArthur had rushed down to their assistance before being washed away himself. But if he had left the lighthouse in a panic, why had he wasted precious time on closing both the entrance door and the gate to the yard?

Thomas Marshall was said to have written the following logbook entries:

Thomas Marshall logbook entries

But, the book “The Lighthouse” by Keith McCloskey points out, "It is extremely unlikely that he would have written in the official logbook that his superior was 'irritable.’” The earliest instance of the entries that McCloskey could find was in a 1965 book by Vincent Gaddis, the sensationalist American writer who first named the phenomenon of the "Bermuda Triangle".

McCloskey concludes that the most likely outcome is that one of the men fell from the steep steps carved into the Western cliffs while trying to secure some equipment in a storm. (Ducat had previously been fined five shillings for failing to look after his equipment in bad weather and would have wanted to avoid another such fine.) McCloskey speculates that the other two would have tried to rescue him, but a giant wave would have washed away all three.

Violence between the three men resulted in murder

McCloskey wrote about the story around Donald John Macleod, a part-time harbourmaster who occasionally worked at the lighthouse and was there when WWII started.

One day, Macleod was working there with two other men when one succumbed to severe flu, and another had a mental breakdown. The book says, "He tried to keep everything running on his own until the arrival of the relief on the Pole Star [a relief ship], which was four days away. The mentally unstable lightkeeper had threatened violence... which resulted in them having to overpower the out-of-control lightkeeper and tie him up."

Could something similar have happened to the keepers in 1900? MacArthur was said to have a volatile temper, but there is no evidence of such an attack, such as blood or evidence of a fight.

Kidnapped off the island by Pirates or a foreign power

This is considered unlikely as by the early 20th century, kidnappings from Scotland by pirates were largely eliminated.

For over 300 years, the coastlines of the southwest of England were at the mercy of Barbary pirates (corsairs) from the coast of North Africa, comprised of North Africans but also English and Dutch privateers. They were based mainly in the ports of Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli, and they aimed to capture slaves for the Arab slave markets in North Africa.

Barbary pirates attacked countries bordering the Mediterranean and the English Channel, including Ireland, Scotland, and Iceland. They almost raided the western coast of England at will.

In response, in 1675, British, French and Spanish warships attacked the pirates. The United States fought two wars against the Barbary States of North Africa: the First Barbary War of 1801–1805 and the Second Barbary War of 1815 – 1816. Finally, after an attack by the British and Dutch in 1816, more than 4,000 Christian slaves were liberated, and it was the end of the Barbaby kidnappings.

Supernatural dark forces

The island has long been associated with the supernatural. Subsequent lighthouse keepers at Eilean Mor reported strange voices in the wind calling out the names of the three dead men.

The Vanishing Movie 2018

A film called “The Vanishing” covers the 1900 Flannan Isles mystery. It starred Gerard Butler as James Ducat, Peter Mullan as Thomas Marshall, and Connor Swindells as Donald MacArthur. The film was directed by Kristoffer Nyholm, best known for the Scandinavian drama The Killing.

Principal photography on the film began in mid-April 2017. Three lighthouses in Dumfries and Galloway were used for filming locations - Killantringan, Mull of Galloway and Corsewall, and Cloch in the Firth of Clyde. They also filmed in Port Logan, which was said to have many features similar to the Isle of Lewis harbour, where the men would have sailed to the Flannan Isles.

Wikipedia describes the plot as follows:

Three men begin their six-week shift tending to the remote Flannan Isles Lighthouse. Donald, the youngest, is inexperienced and is learning the trade of lighthouse keeper from James and Thomas. James has a family waiting for him on the mainland. Thomas is still mourning the loss of his wife and children.

After a storm, the men discover a boat, a body and a wooden chest washed ashore. Donald descends the cliffs to check on the man, who appears lifeless. As they haul the chest, the man awakens and attacks Donald, who smashes the man's head with a rock in self-defense.

Thomas is against opening the chest but does so alone and keeps the findings to himself. Eventually, the other two men surrender to their curiosity and discover several gold bars inside. Urging caution and secrecy, Thomas proposes they dispose of the body, sneak the gold back to the mainland, and lie low for a year before splitting their shares.

Another boat arrives with strangers Locke and Boor, crewmates of the deceased. They interrogate Thomas, who claims the body and cargo have been reported and taken away, as per protocol. The visitors leave but attempt to contact the lighthouse by radio. Thomas and James cannot respond due to their malfunctioning radio, revealing their lie. The strangers return, circling the island until nightfall. In a violent struggle, James manages to strangle Boor, and Donald kills Locke using the woolding. Sensing another intruder outside, the keepers chase him through the darkness, and James slashes him with a hook. He is horrified to discover he has killed a young boy, reminding him of his son.

After dumping the bodies into the sea, the three men endure their remaining time on the island despite mounting distrust and tension. James, in particular, becomes unhinged, secluding himself in the tiny chapel nearby. Donald grows uneasy and insists that he and Thomas leave with the gold. James suddenly reappears, apologising for his behaviour. Once Donald and Thomas let their guards down, James locks Thomas in the pantry and strangles Donald. Thomas breaks free and subdues James.

Finally ready to depart the island, Thomas and James board the dead visitors' boat with the gold. After throwing Donald's body overboard, James admits that he cannot bear to live with his guilt and lowers himself into the water to end his life. He calls for Thomas to help with this last act, and Thomas complies by holding James' head under the water before sailing on alone.

Read more strange stories from Scotland

The strange and unexplained death of Nicholas Randall in the Scottish Highlands

The disturbing death of Fiona Torbet in the Scottish Highlands

The mysterious case of Netta Fornario on the Scottish Island of Iona

The strange disappearance of Shaun Ritchie from Scotland on Halloween Night

The Great Mull Air Mystery - The death of Peter Gibbs on the Isle of Mull in Scotland (Member only)

The strange disappearance of the YouTube Survivalist Finn Creaney in the Scottish Highlands

Exclusive articles for members of StrangeOutdoors that are not available elsewhere on the site.

See the latest list of Exclusive members-only articles on StrangeOutdoors.com

Further reading

The Lighthouse Paperback – July 22, 2014 by Keith McCloskey

Sources

https://locationsunknown.podbean.com/e/ep-21-eilean-mor-lighthouse-keepers-scotland/

https://www.nlb.org.uk/history/flannan-isles/

https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofScotland/The-Eilean-Mor-Lighthouse-Mystery/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flannan_Isles_Lighthouse

https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/article/our-records-shining-light-lives-lightkeepers

https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/research/research-guides/research-guides-a-z/lighthouses

https://www.history101.com/eilean-more/

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-6922197/New-film-attempts-answer-caused-three-lighthouse-keepers-vanish-night.html

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-south-scotland-47732497

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/films/0/vanishing-happened-flannan-isles-lighthouse-real-mystery-behind/